Condividere un sogno,

su una scala mobile

La storia e le motivazioni che hanno portato alla realizzazione di una fotografia famosa che, da sola, riassume e racconta i principi del Realismo estetico

Sono stato colpito profondamente da Martin Luther King, nel 1963, quando, ragazzo ebreo 13-enne di Brooklyn, vidi in televisione il suo discorso alla marcia su Washington; ricordo soprattutto la frase:

"... quando lasceremo che risuoni la libertà, quando faremo sì che si espanda

da ogni caseggiato e da ogni frazione, da ogni stato e da ogni città,

saremo in grado di accelerare il giorno in cui tutti i figli di Dio,

tutti gli uomini neri e bianchi, ebrei e gentili, protestanti e cattolici,

saranno in grado di unire le mani e cantare le parole del vecchio spiritual:

"Liberi finalmente, finalmente liberi. Grazie a Dio Onnipotente, siamo finalmente liberi."

Gli anni sono passati ed ho potuto constatare che l'appassionato appello che colpì me, e milioni di altre persone, si collegava anche all'arte che mi appassiona tanto: la fotografia.

Nel 1975, ero un giovane fotografo e ho iniziato a studiare il Realismo Estetico, imparando che ogni esempio di bellezza nell'arte - dalla prosa passionante, ad una buona fotografia - ci può insegnare come il mondo e le persone meritino di essere visti.

Eli Siegel, il fondatore di questa grande filosofia, il Realismo Estetico, ha dichiarato:

“ Tutta la bellezza è l’unire gli opposti e l’unire gli opposti è ció che cerchiamo per noi stessi”.

Amo questo principio, perché dimostra che la bellezza è reale e pratica come il marciapiede su cui camminiamo, e che noi non solo vogliamo essere come l'arte - ma possiamo esserlo!

Nel 1983, quando ho sentito che stavano organizzando la "marcia su Washington per posti di lavoro, pace e libertà" celebrazione del ventesimo anniversario del famoso discorso di Martin Luther King: "I Have A Dream", ho deciso subito di parteciparvi.

Sapevo che sarebbe stato un appuntamento storico e volevo rappresentarlo giustamente da fotografo. Così ci sono andato, anche per i consigli di Nancy Starrels, di cui avevo frequentato il corso di fotografia, The Honoring Eye, presso la fondazione del Realismo Estetico a New York City.

Proprio lei mi aveva suggerito di pensare profondamente al significato di quella giornata e di come avrei potuto dargli forma con una singola fotografia. Questo ha contribuito a chiarire il mio pensiero circa la storia stessa del razzismo e su come le persone bianche e nere potevano sperare, o disperare, nel cambiamento.

Ho imparato, anche, che la fotografia dà senso a questi opposti: speranza e disperazione, luce e buio, uniformità e differenza. La mia emozione sul significato della marcia è cresciuta quando ho pensato a come l'unità degli opposti, nell'arte della fotografia, avesse la risposta a ciò che affligge le persone.

Quello che ho visto a Washington, ha avuto su di me un'impressione durevole. Ho visto persone di razze e religioni diverse, giovani e vecchi, benestanti e poveri, marciare insieme in nome di un'America giusta per tutti.

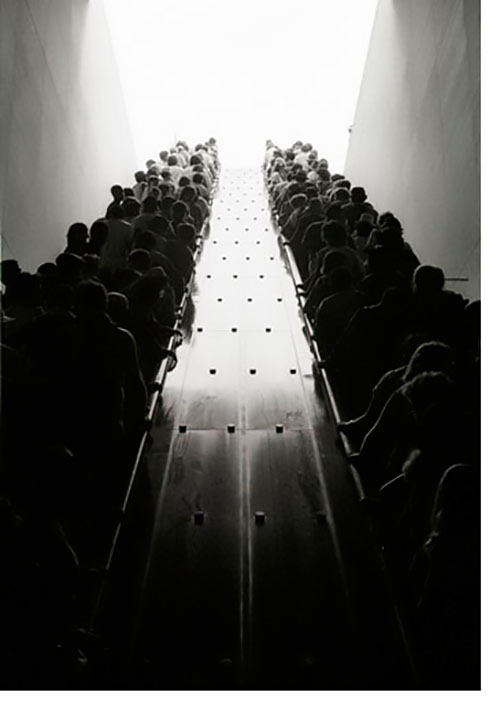

Ho assistito a molti episodi che mi hanno commosso. Tuttavia, c'è una scena che mi ricorderò per tutta la mia vita: manifestanti su una scala mobile, mentre tornano a casa, tutti riuniti come se uscissero dalle tenebre verso la luminosità radiante. Questa era la foto che cercavo!

Successivamente, compresi meglio cosa mi aveva colpito studiando lo storico saggio di Eli Siegel: “Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?" con questa domanda su Somiglianza e Diversità.

Dimostra ogni opera d’arte un’affinità che si trova negli oggetti e in tutte le realtà?

Ed al tempo stesso la diversità, sottile e tremenda,

il dramma di ció che é altro, si puó trovare tra le cose del mondo?

Quando ho scattato questa foto ero entusiasta del contrasto di luce e buio nella scena, e nella gente, e come, allo stesso tempo, tutti si confondevano l'uno con l'altro, unendosi a vicenda. Con tutta la loro differenza, luce e buio non lottano tra loro. C'è "affinità" e le persone sembrano fondersi nel buio. Quindi, come la luce delinea una mano su una ringhiera, la linea di una spalla, il profilo di un volto, vediamo in queste forme, uniche, individuali, "il dramma dell'altro". Mentre guardiamo a questi uomini e queste donne, possiamo dire chi è bianco e chi è nero? Sono tutti "figli di Dio".

Il Realismo Estetico spiega che il razzismo inizia con il desiderio delle persone di provare disprezzo, "di pensare che sia meglio per noi stessi il diminuire il mondo esterno."

É il sentimento: "Loro sono tutti uguali, ma io sono diverso, più sensibile, superiore, e ho il diritto di trattare con loro nel modo che pare a me."

Questo brutto atteggiamento prende migliaia di forme ordinarie. Per esempio, come quello della mia famiglia seduta attorno al tavolo della cucina a Brooklyn mentre parlava delle altre persone, spesso con un senso di superiorità. Giudicandoli tutti: i vicini, i colleghi, i compagni di scuola, come se avessero carenze che li hanno resi inferiori a noi (così come ci giudichiamo noi stessi).

Non avevamo idea che la nostra superiorità immaginata era il motivo che ci portava a litigare e a far sentire ognuno di noi solitario e vuoto. L'accumulo del disprezzo, portato avanti sufficientemente, ci porta all'ingiustizia e al razzismo.

L'idea che possiamo essere più completi anche accogliendo la differenza degli altri, si è diffusa tra le persone da molto tempo. Ma, alla fine, come si può superare l'intolleranza e il razzismo? Ellen Reiss, Chairman of Education del Realismo Estetico, in proposito ha scritto nel periodico internazionale The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known:

"... il razzismo non potrà essere spazzato via efficcacemente, a meno che non venga sostituito con qualcosa che abbia un potere straordinaario. Che cosa deve sostituirlo non è la sensazione che la differenza di un'altra persona è, in qualche modo, tollerabile. Ciò che è necessario è comprendere e sentire che il rapporto di identità e differenza tra noi e le altre persone è bellissimo".

Il Realismo Estetico mi ha insegnato che gli opposti non devono combattersi, che ogni esempio dell'arte mostri come gli opposti possano essere profondamente amichevoli e che in questo vi è il modo giusto di vedere la gente che farà finire il razzismo per sempre! Per esempio, buio e luce in una fotografia non si tollerano a vicenda. Ma hanno bisogno l'uno dell'altra e valorizzano le vicendevoli buone possibilità.

In questa foto la luce mette in evidenza l'unicità della gente, in basso, ancora nel buio; mentre è il buio che rende gradualmente possibile vedere la gente che si avvicina al cielo. E vi è anche dello “humor“ con i piccoli rotondi pezzi di metallo in centro con la loro luce e tenebra che marciano verso l’alto con la gente ai loro lati.

L'inclinazione verso l'alto della fotocamera, con l'obiettivo grandangolare 35mm, ha fatto sì che le due scale mobili convergano. Così le persone sui lati opposti appaiono sempre più vicine, man mano che si approssimano alla cima, dove le pareti pesanti di calcestruzzo si dissolvono nella luce, espandendosi verso l'esterno.

Ho avuto la sensazione che tutte queste persone stessero andando verso un mondo più luminoso, un mondo più gentile, un mondo in cui credo fermamente e che il realismo estetico può rendere reale.

Ecco, nella mia fotografia ho cercato di mostrare proprio questa sensazione.

English version:

People on an Escalator Share a Dream

by Len Bernstein

I was stirred deeply by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1963 when I, a 13-year-old Jewish boy in Brooklyn, saw his televised speech at the March on Washington, where he said:

…when we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every tenement and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old spiritual, "Free at last, free at last. Thank God Almighty, we are free at last."

As years went on, I came to see that the passionate justice which stirred me and millions of others, had to do with the art I care for so much: photography.

In 1975, as a young photographer, I began to study Aesthetic Realism, and learned that every instance of beauty in art—from stirring prose, to a good photograph—can teach us how the world and people deserve to be seen. Eli Siegel, the founder of this great philosophy stated, “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” I love this principle because it shows that beauty is as real and as practical as the pavement we walk on, and that we not only want to be like art—we can be!

In 1983, when I heard plans for the “March on Washington for Jobs, Peace, & Freedom” celebrating the 20th anniversary of Dr. King’s immortal “I Have A Dream” speech, I was eager to go. I knew it would be historic, and I wanted to be fair to it as a photographer. And so, I went for advice to Nancy Starrels, whose photography class, The Honoring Eye, I attended at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation in New York City. She advised me to think as deeply as I could about the meaning of that day, and how I could give it form in a single photograph. This helped to clarify my thought—about the history of racism itself, and how black and white people can both hope for and despair of change. I learned, too, that photography makes sense of these opposites: hope and despair, light and dark, sameness and difference. My emotion about the meaning of the march grew as I thought of how the oneness of opposites in the art of photography has the answer to what plagues people.

What I saw in Washington made a lasting impression on me. I saw people of different races and faiths, young and old, well-to do and poor, marching together in behalf of an America just to all people. I witnessed many things that moved me. However, there was one scene that I’ll remember all my life—marchers on an escalator, returning home, all joined together as they rose from the darkness below to the radiant brightness above. This was the picture I was looking for!

Later, I better understood what had affected me as I studied Eli Siegel’s historic essay, Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? with these questions about Sameness and Difference:

Does every work of art show the kinship to be found in objects and all realities?—and at the same time the subtle and tremendous difference, the drama of otherness, that one can find among the things of the world?

When I made this photograph I was thrilled by the contrast of light and dark in the scene and the people, and how, at the same time, they mingled with one another, added to each other. With all their difference, light and dark do not fight. There is “kinship” as people seem to merge in the dark. Then, as light outlines a hand on a railing, the gentle slope of a shoulder, the profile of a face, we see in these unique, individual forms, “the drama of otherness.” As we look at these men and women, can we tell who is white and who is black? They are all “God’s children.”

Prejudice begins, Aesthetic Realism explains, with the desire in people to have contempt, “to think we will be for ourselves by making less of the outside world.” It is the feeling “They are all the same, but I’m different, more sensitive, superior—and I have a right to deal with them any way I please.” This ugly attitude takes thousands of ordinary forms. For example, as my family sat around the kitchen table in Brooklyn and talked about people, it was often with a sense of entitlement. We summed them up, and saw neighbors, co-workers, schoolmates as having shortcomings that made them inferior to us (we saw each other that way, too). We had no idea that our imagined superiority was the reason we argued with each other and why we each felt lonely and empty. The accumulation of contempt, carried far enough, makes for every injustice, including racism.

The idea that we can be more complete through welcoming the difference of others has resonated with people for a very long time. Yet, how can intolerance and racism finally be overcome? Ellen Reiss, Aesthetic Realism Chairman of Education, writes in an issue of the international periodical The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known:

…racism won’t be effectively done away with unless it is replaced with something that has terrific power. What needs to replace it is not the feeling that the difference of another person is somehow tolerable. What is necessary is the seeing and feeling that the relation of sameness and difference between ourselves and other people is beautiful.

Aesthetic Realism taught me that opposites don’t have to fight, that every instance of art shows how deeply friendly they can be, and within this is the just way of seeing people that will end racism forever! For instance, dark and light in a photograph don’t tolerate each other. They need each other and bring out good possibilities in each other. Here light brings out the uniqueness of people in the dark below while it is darkness that makes it gradually possible for us to see the people as they meet the sky. And there’s humor as little round pieces of metal in the center, with their own light and dark, are marching upwards along with the riders on either side.

The upward tilt of the camera with its 35mm wide angle lens causes the two escalators to converge. This brings people on opposite sides closer as they reach the top, where heavy concrete walls dissolve in the light and also expand outward. I felt all these people were going toward a brighter, kinder world—a world I passionately believe Aesthetic Realism can make a reality. I tried to show that feeling in my photograph.

Note: Photographer Len Bernstein began his study of Aesthetic Realism in 1975 in consultations with The Kindest Art, and later with the founder of this philosophy, Eli Siegel. His study continues in classes taught by Chairman Ellen Reiss at the not-for-profit Aesthetic Realism Foundation in New York City (www.AestheticRealism.org). He has written, lectured, and teaches photography in relation to ethics, and his photographs are in many private and museum collections.